On Friday, the UN General Assembly adopted new recommendations that fell far short of the more ambitious reforms put forward by governments this year on the selection of the organization’s top post.

As discussed previously, a large part of the rules surrounding selection of the UN Secretary General stems from a UN General Assembly resolution adopted in 1946. The resolution defined the term of office (5 year, renewable), provided for a single nominee from the Security Council, and required a simple majority vote in the Assembly for appointment.

None of this changed on Friday.

The Assembly adopted its lengthy and perennial Report of the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Revitalization of the Work of the General Assembly, including provisions on how it intends to jointly select the Secretary General with the Security Council. Despite efforts by Costa Rica, India, members of the Non Aligned Movement, the ACT Group of States, and others, the Assembly failed to include a call for multiple nominees for consideration by the Council or a single 7- or 8-year non-renewable term for the next office holder.

These two reforms would have had the greatest impact in shifting influence both in the selection and in the office of Secretary General itself. Neither made it into the resolution text.

Though the Assembly can reject the Council’s single nominee, it has never done so and is unlikely to take such political action by the necessary majority. The office will continue to be more “secretary” than “general” as the incumbent will seek re-nomination by the Council five years hence. Any candidate that pledges to serve even a single 5-year term will no doubt be vetoed by one or more permanent members unwilling to accept such independence.

The resolution did call for improvements on the front end of the process. These included providing

for a joint letter from the Presidents of the Council and the Assembly to formally invite nominations, and calling for criteria to be met by candidates, including “proven leadership and managerial abilities, extensive experience in international relations, and strong diplomatic, communication and multilingual skills.”

If implemented in ways envisioned by the 1 for 7 Billion campaign and others, these may lead to a more qualified slate initially. However, as important as these improvements are, the resolution’s recommendations otherwise suggest the outcome will not be improved in meaningful ways this time.

The decision to encourage candidates to engage with non-Council members in “informal dialogues” is hollow at best. Such is more likely to emerge through the perogative of the candidates and their governments than from the resolution, and will have no impact on the outcome in any case given the continued weak role to be played by the Assembly.

There is no call for a formal process by the Council is keep the Assembly informed of its considerations during its process. Straw poll results emerged only through leaks during the 2006 race, but reform advocates were unsuccessful in urging a more codified process this year.

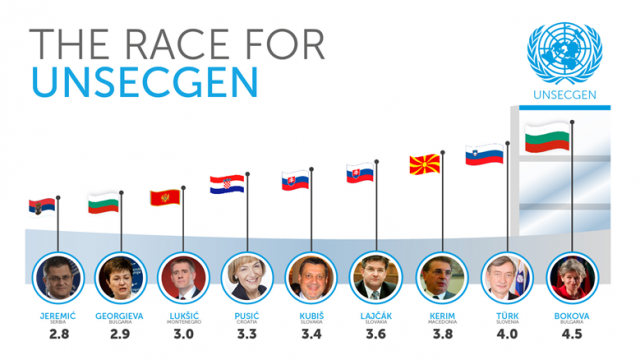

Gender equality as a goal may be the one endorsement where a notable impact on the process could occur, in that it is likely to directly influence which nominees are put forward by governments. Initially introduced in the 1990s, this goal was almost universally supported by member states in discussions this year. However, there is no obligation on the part of governments or the Council to put forward a female nominee any more than they are required to put forward a nominee from the Eastern Europe group. The Council will be harshly and rightfully criticized by advocates should the single nominee be a male and/or from another region, but no one expects the Assembly to reject such a nominee or demand another.

Given these endorsements however, the question now turns to how the Council will internally consider candidates and move toward a nomination. Perhaps inadvertently, the resolution will push back the formal process until at least November by calling for a joint letter from the Presidents of the Council and the Assembly. Ambassador Román Oyarzun noted in July that discussions on the working methods of the Council—an allusion to how the nominations would be vetted by the Council–would take place during Spain’s presidency of the Council in October. As such, any joint letter will not appear until mid-November or later. The United Kingdom, which supports a joint letter among proposed reforms, hold the Council presidency in November.

Should the Council adopt a process that involves a deadline for nomination—heavily pushed by reform advocates but noticeably missing from the Assembly’s recommendations—it would be no earlier than February or March of next year, followed by a series of straw polls leading to the final decision in the summer.

Unlike processes in other multilaterals–referenced in the resolution–the vetting of candidates for the position of Secretary General is not likely to encourage or require those with the least number of straw votes to withdraw. As such, the penultimate if not all straw ballots will be color coded so as to identify with certainty those candidates who will be vetoed in the Council’s official vote. At that point, a mass withdrawal of candidacies will occur by all but the “sole” candidate for the post.

This nominee, having survived the threat of a veto, will be nominated — and for all intents and purposed, appointed — by those states sitting on the Council next year. These include the permanent members China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, plus rotating members Angola, Egypt, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Spain, Ukraine, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

The nominee will received the Council’s approval by acclamation. With the Assembly’s failure to substantively update the 1946 resolution, this person will be the single nominee offered to the Assembly. Once rubberstamped, the new head will likely head the world organization for the traditional two 5-year terms, through 2025.

2 thoughts on “General Assembly Falls Short on Reform”

Comments are closed.