Later this year, the international community will select the next United Nations Secretary-General. More accurately, per Article 97 of the UN Charter: “The Secretary-General shall be appointed by the General Assembly upon the recommendation of the Security Council.”

The past being prologue, the most powerful countries, notably the Security Council’s five veto-wielding permanent members China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, will exert major influence over the decision. Historically, the General Assembly has accepted by acclamation the Council’s single recommendation. The reappointment of Trygve Lie in 1950 by a majority vote of the General Assembly without a recommendation by the Security Council remains the exception to the rule.

Nonetheless, for at least three reasons, some much needed reforms are underway in the selection process: first, the General Assembly has asserted a larger role well in advance of the Security Council’s consideration this year; second, civil society is better organized, notably through the 1 for 7 Billion Campaign; and lastly, an effective UN Secretary-General is increasingly viewed more than ever as critical to good global governance.

On September 11, 2015, the UN General Assembly unanimously adopted Resolution 69/321, which is of seminal importance as for the first time:

- It sets out basic selection criteria to ensure “the appointment of the best possible candidate for the position of Secretary-General.”

- It called for the selection process to be initiated by a joint letter from the President of the General Assembly and President of the Security Council.

- It urged that the full UN membership receives the list of candidates under consideration and be given an opportunity to engage and question them prior to the Council’s final deliberation.

On December 15, 2015, General Assembly President Mogens Lykketoft and U.S. Ambassador Samantha Power, holding the Council presidency, issued a letter marking the start of the selection process and reconfirming Resolution 69/321’s guidance. And this past week near New York, the General Assembly President convened a high-level retreat, with current and former senior government officials, as well as scholars and civil society representatives, to feed further ideas into making the selection process more transparent and inclusive.

It is difficult to imagine such rapid progress without the targeted pressure of civil society groups—termed the “Third UN” by global governance scholars Thomas Weiss, Tatiana Carayanis, and Richard Jolly—beginning with those participating in the 1 for 7 Billion Campaign. Initiated in 2014, the campaign now boasts the participation of 750 organizations with a combined reach of more than 170 million worldwide, including Amnesty International, the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (New York), Parliamentarians for Global Action, and the World Federalist Movement. In addition to many of the reforms called for in Resolution 69/321, the campaign calls for other innovations, such as letting parliaments and civil society organizations (in addition to Member States) propose candidates for Secretary-General; recommending that nominees outline their policy priorities and commitment to select senior UN officials on the basis of merit, irrespective of their country of origin; and encouraging the Security Council to present more than one candidate for the General Assembly to consider.

Another significant factor putting wind into the sails of reform is the growing global interest in UN governance after world leaders, gathered by the United Nations in 2015, reached consensus on the monumental 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Paris Agreement on climate change. To deliver on their historic commitments, attention now turns to the effectiveness of the United Nations in marshalling the resources, ideas, networks, and talents of diverse transnational actors, from states, regional organizations, and municipalities to business and civil society groups. Leadership at the top of the world body is also needed urgently to cope with concurrent global crises, from growing mass violence in fragile states and alarming refugee flows to fears of devastating cross-border economic shocks and cyber-attacks. To better deal with each of these global policy challenges, the next Secretary-General will need to continue to work in close partnership with states, especially the most powerful states.

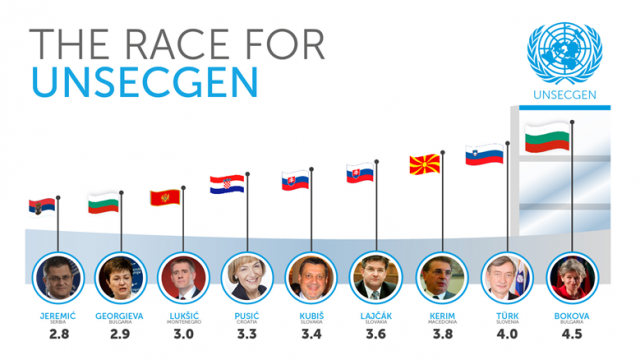

The incremental, yet important reforms put in play through Resolution 69/321, including its invitation to Member States to present women as candidates for Secretary-General, may lead to a more transparent and inclusive process and a better outcome. Many exciting potential nominees, especially female candidates such as UNESCO’s Irina Bokova, UNDP’s Helen Clark, and the Secretary-General’s former Special Adviser on Post-2015 Development Planning Amina Mohammed, are highly regarded—more details on other prospective female candidates can be found through the Campaign to Elect a Woman UN Secretary-General.

But the progress achieved in recent months only marks the beginning of what should be a critical process of renewal and transformation in the UN Secretariat. For instance, the high-level Commission on Global Security, Justice & Governance, supported by The Hague Institute for Global Justice and the Stimson Center, recommends: “consideration of a single, seven-year term for the Secretary-General. This would enable the Secretary-General to focus more on meeting performance, rather than political, goals during the term.” The General Assembly may take up this idea in the next session of its Working Group on Revitalization.

The Commission further calls for empowering the Secretary-General with more discretion to manage the Secretariat (including in hiring and firing staff). It also supports a second Deputy Secretary-General to forge greater UN system-wide coherence in the areas of economic, social, and environmental policy and programming—freeing up the other Deputy to better support the Secretary-General on critical matters of peace and security. Other ambitious UN and broader global governance reforms are presented in the Commission’s report Confronting the Crisis of Global Governance.

Yet a far-reaching program of urgently needed global reforms is unlikely to take root without new coalitions of civil society groups and like-minded UN Member States. The momentum behind UN Secretary-General selection reform offers hope that the international community will appoint a courageous and visionary leader, with the necessary diplomatic skills, broad networks, and political clout with the most powerful states, to help make this happen.

This was originally posted on The Hague Institute’s website on 14 January 2016. Crossposted with permission of the author.